On the qualities of chaos, the chances of the digital and the importance of radical reboots.

A thunderstorm tore me out of my heavy Alpbach-sleep, that kind of numbness you surrender to, defeated by the wave of lectures, discussions and late Gasthaus-nights that flood the village every year in August. This was the last day of the European Forum Alpbach.

I pull the curtain. Those ever same Alpbach houses pretending to be part of a time long forgotten. Heaps of furious rain hitting their roofs from a gray illuminated sky that does not promise well. And a slope covered with long grass wildly dancing in the storm. An uncanny picture, of a world that is out of balance. People like me started to move around the globe to random places like this, the weather became wilder than ever before, and at some point the border between culture and nature, authentic and fake simply became irrelevant. Total chaos, and we still didn’t quite understand how to navigate it.

Disturbing to most, this weather is a perfect scenery for my final mission here in Alpbach, the moderation of a small breakfast session with Prof. Eyal Weizman who spends his days fighting for human rights in tormented war zones.

This place must have been quite alienating to him:

As an Israeli architect investigating spatial evidence of war crime between blooming Tyrolean balconies; As a keynote speaker on architectural traces of human rights violation among generic and half-hearted discussions on subsidized housing in Vienna;

But Eyal Weizman is probably comfortable in feeling out of place: with his research Agency Forensic Architecture (Goldsmiths, University of London), he founded an entirely new field of expertise. Instead of constructing, he deconstructs; his clients are not investors or municipalities but international prosecutors, human rights organizations, as well as political and environmental justice groups.

This morning, we sit in a equally suiting gloomy old Stube at Messner’s, drinking Austrian coffee. Weizman and a small group of Alpbach survivors.

A Forensic Architect relates to an architect like a pathologist to a medical doctor, he explains: he reconstructs a series of actions by analyzing traces on buildings and cities.

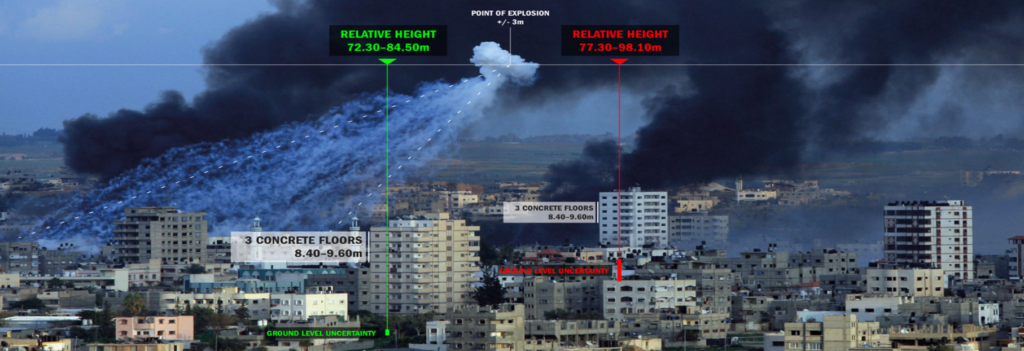

Forensic Architecture: deconstructing urban battlefields (Foto: http://www.forensic-architecture.org/cases/)

Weizman claims that the field had become necessary, because unlike historic battlefields in free nature, contemporary conflicts increasingly take place within urban areas.

Homes and neighborhoods so become targets and most civilian casualties occur within cities and buildings. At the same time, urban battlefields have become dense data and media environments, generating information that is shared on social and mainstream media.

Forensic Architecture absorbs this stream of visual information and uses it to model dynamic events as they unfold in space and time. Their products therefore are not buildings, but navigable 3D models of environments undergoing conflict, filmic animations and interactive cartographies on the urban or architectural scale.

There is something extremely fascinating about the unsettling nature of Weizman’s work. After days of talking about digitization and robotics here at the Forum, finally we hear how contemporary visual culture and digital are an instrument to both democratize and hack large power systems.

Asked about the beginnings of his unusual career, Weizman describes how as a young architect he was asked to curate an exhibition in Berlin featuring the best of Israeli architecture. Finding, as he says, nothing more annoying than architects’ egos, he refrained from giving them yet another platform, and used the entire budget on neatly documenting Israeli settlement strategies in Palestine. The exhibition was canceled, all catalogs destroyed, and Weizman highly satisfied.

“I have the feeling that in my work I need to be very close to evil” he thinks out loud, reflecting on what still drives him. Forensic architecture sheds light on the darkest corners of human nature and designs powerful systems to give control and information back to the weak, the civilian victim. Weak up, he says, things are really quite bad in this world if you are honest to yourselves – and starts to deflate the Alpbach-bubble.

So, what can one person do? somebody asks.

Think radical. It is always difficult to change things downstream. As an ordinary architect for instance, your ability to impact is limited to a tiny fragment of space caged by a very elaborate corset, result of a chain of decisions producing legal, social and economic constraints. How much can you do, how far can you think from this place? You have to start questioning the very top, the premises.

Somehow things came full circle that last day.

Maybe this formless reality after graduation in the end was a good place to be. After all, it very well represents our time, unstable, overcrowded with information, on the search for meaning.

To most, if they admit it or not, there is little more scary in life than setting your own constraints and drawing your bold path towards the unknown. Maybe it is exactly here, in the chaos of truths, longings and opportunities that we have to most defend who we are and what we want to be in this world.

Veronika Mayr

Deutsch

Deutsch